Soldiers of the Soil

British horticulturist Gertrude Jekyll once said “A garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all it teaches entire trust.” Alice Hand Callaway believed that gardening taught her “patience, perseverance, and acceptance.” These traits were also valued by Fuller E. Callaway Sr., not just in gardening, but also in business. He believed providing spaces for mill families to plant gardens and flowers, as well as community greenhouses, was “good business” and would help to keep employees satisfied and productive. Fuller’s idea for a garden-laden community was not completely new. The first community garden in America can be traced back to the 1890s in Detroit, Michigan. The city sponsored urban gardening programs in vacant lots as a response to the economic recession which had left many unemployed and hungry. Upon entering World War I in 1917, the U.S. War Garden Commission made growing one’s own food a patriotic act by calling on citizens to become “soldiers of the soil.” Over 3.5 million gardens were created, producing around $350 million worth of crops. Due to the Commission’s success, the government supported a similar national campaign almost thirty years later at the onset of World War II. They cited the health, recreational, and even morale-boosting effects of gardening as well as the practical benefit of providing food during rationing. Reports estimate that by 1944, around 20 million families tended to these victory gardens, providing 40 percent of the vegetables in America during that time. Eleanor Roosevelt famously planted hers on the White House front lawn.

Fuller Sr. may not have specifically used gardening as a way to combat social and cultural issues like war and economic recession, but he did believe it served a great purpose. In the early days of Unity Mills, sections of land were blocked off around the residential areas to serve as individual plots for mill families. Everything needed to start a garden, from seeds and plants to instructions and encouragement, was provided. Gardening clubs sponsored by the YMCA and LaGrange Settlement encouraged children to participate and offered instructions in techniques. Canning clubs also formed to teach children, often young girls, how to preserve the fruits and vegetables grown by their families. Fuller Sr. believed so fully in the link between plants and happiness that he claimed a garden and greenhouses could keep his workforce stable. He would often tell a story of the wife of one of his best workers, who refused to let the family move to another mill because she did not want to lose her plants in storage at the Callaway greenhouses.

The Southwest LaGrange Improvement Association, under the direction of George Weathersbee, encouraged gardening among the mill families from its start in September 1916. They provided flowering and vegetable plants to mill workers free of charge, built greenhouses for the storage of these plants during the winter, and offered instructions on cultivation and care. The Association was also concerned with the appearance of the mill workers’ houses, specifically flowers both inside and outside of the homes. Winners of sponsored contests received awards for things like the biggest vegetables, most attractive cans of prepared food, prettiest “yard garden,” and even “most improved” garden. Cash prizes were often given with the awards. After the Association’s dissolution, the Industrial Relations Department of Callaway Mills took over the gardening activities, including the greenhouses and vegetable and flower contests. The Callaway Beacon, a mill employee magazine published from 1949 through 1969, often listed planting suggestions at the beginning of each growing season, gave information on overwintering in the Callaway Community Greenhouse, and often featured interesting stories on specimens grown by the mill employees. Undoubtedly, the focus on horticulture helped boost workforce morale, added

beauty to the city, and enhanced the quality of life of its citizens. After all, it is the “City of Elms and Roses!”

GARDENING INSPIRATION CONTINUES TODAY

The gardens at Hills and Dales Estate may be known for their picture-perfect blooms and evergreen boxwood, but they also have always served a practical use. Each family that has lived on this property had a vegetable garden, and although it’s no longer a private residence, that tradition still continues. During the Ferrell’s tenure and even through the first generation of Callaway ownership, it was a common part of life—in order to eat well, most people grew a high percentage of their own food. Now, vegetable gardening has become a hobby for the most part; however, a revival of interest in growing one’s own and locally sourced food has catapulted the pursuit into a “trending” pastime.

As for the history of growing for sustenance at Hills and Dales, aerial photos from the 1920s indicate a large vegetable garden was located then where the Ray Garden is now. Alice Callaway converted this space over to ornamentals beginning in the ‘50s, but she didn’t stop cultivating food crops— rather, she moved that operation to an area west of the greenhouse, which is where the vegetable garden is currently. Her records indicate that she planned for and cultivated a variety of produce every year. Reportedly, she and her daughter, Ida Callaway Hudson, would vie for who would produce the first tomato of the season, and thereafter, whose crop might be superior in some way to the other’s. Other favorites of hers were muskmelons, a large white running lima, Malabar spinach (a hot weather spinach substitute), eggplant, peppers, lettuce, turnips, and mustard greens. The story about the year she grew a small patch of sweet corn was relayed in Portico issue #26. Apparently it was a rousing success, but only for the squirrels!

After the estate opened to the public, the horticulture staff was charged with continuing to grow a vegetable garden, and although it isn’t as large as in previous times, one is planted every year. Summer produce predominates, but greens, lettuce, kale and other cool season crops are often sown as well. We’re frequently asked to give gardening tips, so the following are five pointers that were each a strategy Alice used for success:

1. The first is to PLAN. This article is coming at a most opportune time, because the approaching fall season is an ideal time to begin thinking about what crops to plant and where to put them. If you already have a designated space, there is time to do some preparation and have a fall garden. If you are a novice, we recommend starting small and easy. There are food crops that are relatively simple and nearly foolproof to grow which are perfect for beginners, so you can learn and gain the confidence to try more demanding ones.

2. Next is to SITE PROPERLY. If there isn’t a designated space for growing vegetables, assess your property, and determine where a likely spot would be. Plenty of sunshine is generally required—6-8 hours per day. Also, if possible, choose an area that faces south, and orient any rows north to south. This will maximize even sun exposure. Morning sun is ideal and late afternoon shade, provided the sun requirement has been met, is not a bad thing in the Deep South; however, large trees that are too near the garden will likely compete for water and nutrients and shade these sun lovers too much. One other must‒put it where there is close access to water.

3. Take a SOIL SAMPLE from your plot and have it analyzed for pH and major nutrient levels. This is a smart thing to do for any form of gardening, but is especially important for growing vegetables. Although it can be done any time of year, fall is considered ideal. This service is generally offered for a small fee per sample through your county’s Agricultural Extension Office. Once the results are back in, make any recommended amendments according to the instructions.

4. COLLECT hardwood leaves this autumn. Seriously—they are GARDEN GOLD. We’re not sure who taught Mrs. Alice to do this but she used them routinely as a thick mulch, and everywhere they were put our native red, sticky clay eventually turned into dark brown, rich, earthworm-laden topsoil. Leaves are collected here as they start falling every year in the following manner: A] mow over them to reduce their size. This will make them easier to handle for collection and spreading, plus it will also hasten their decomposition rate. B] Gather them in the most practical manner (bagger attached to a mower; windrow and then rake up; get your neighbor’s from the curb, etc.) C] Pile them close to where they’ll eventually be used. As the vegetable garden is emptied of plants

and cleaned up in the fall and early winter, distribute shredded leaves over the area to a thickness of 4-5 inches, which is also enough to deter most weeds.

5. START COMPOSTING. If you have a surplus of shredded leaves, they are great to begin a compost pile or bin with; but even if you don’t, you can create compost with vegetable and fruit peels from your kitchen, pesticide and weed-free grass clippings, coffee grounds, spent flowers, egg shells, shredded newspaper, wood chips… you get the idea. Online instructions and options abound. Once “finished,” compost can be spread around plants for nourishment and for improving soil quality. Its effect is almost magical.

So do you need any more encouragement to join in this ancient, yet once more valiant pursuit? Be careful…gardening in any form can be quite seductive, but once the first fruits of your efforts are tasted, there might be no turning back. -HM & JP

Elm City Greenhouse |

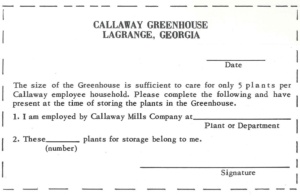

This card was printed in the Callaway Beacon as a means for employees to identify their plants to be stored in the Callaway Community Greenhouse. |

Callaway Community Greenhouse |

In the September 15, 1952, edition of the Callaway Beacon, Jack Kaiser, George Weathersbee, and Nolan Fletcher are pictured holding a large Ponderosa lemon. The lemon came from a tree in the Callaway Community Greenhouse planted by the late C. D. Bledsoe. |

A mill village home featuring beautiful plants and flowers. |

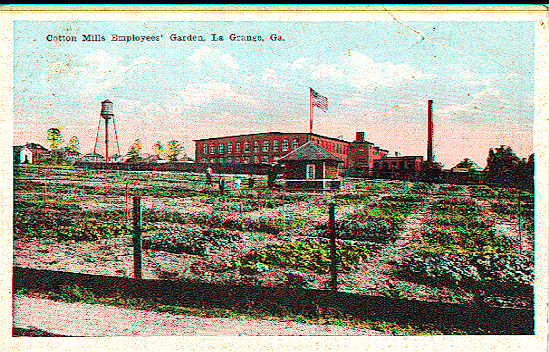

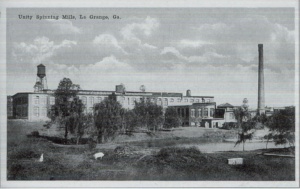

Postcard showing an employee’s garden next to a cotton mill. |

Fuller Sr. also encouraged his employees to own a cow to provide milk and milk products for their families. Each mill set aside a piece of land for use as a common pasture, built barns, and loaned money, interest-free, to employees so they could purchase a cow. |