A Garden Walk with Sarah Ferrell

A couple of years ago, a guest wrote a review of his visit to Hills & Dales, describing his house tour in very favorable, yet conventional terms. Then he ended with the following detail, “Also we had a private garden walk with Sarah Ferrell. What a fine gardener.” He was speaking, of course, about the woman who began a garden on this site in the 1840s that is still extant and thriving today.

Now I seriously doubt he saw an apparition, but he was expressing, however curiously, that his stroll through those historic paths evoked a response that we would have every visitor experience if we could. For beyond seeing beauty, design, and a multitude of plants, our goal is for each to leave with a sense of the heart, soul, and intellect that’s been poured into this garden since its inception. Noting where this guest listed as home brought more gratification, as it was a very small town in middle Georgia—not Oz to the north, the aristocratic coast, or even one of our more prosperous river cities. This observation also brings back to mind the woman he ‘encountered’ on his walk, for though Mrs. Ferrell didn’t hail from any of those presumably more auspicious locales, she managed to create something quite extraordinary at a time when LaGrange and Troup County were barely out of their frontier days. Such a prospect begs several questions concerning what we can know about this singular person and how she was ultimately equipped for such a stunning feat. Fortunately, we have primary and secondary historical sources that help us to sketch this out to some degree.

The first thing to establish is that she was a very well-educated woman. Born in Jones County, Georgia in 1817 as the eldest child of Mickleberry and Nancy Coleman Ferrell, Sarah was first schooled there at Clinton Academy. Her education continued at the Female Academy at Sparta where the subjects of geography, history, geometry, and botany were taught to the girls in attendance there. Clearly, each of those disciplines would serve her well when she later applied them to design her landscape. She was then sent to Scottsborough Female Institute in Baldwin County, a popular boarding school for daughters from affluent Georgia families. There, young ladies were not just taught the traditionally acceptable female courses of sewing, art, and music, but also higher mathematics, science, English grammar and composition, Greek, Latin, and French. It’s readily apparent that Sarah received a decidedly atypical education for a woman during that period of Georgia history, and she knew it. She would later write of the Institute’s headmaster, Dr. Robert Brown, that he “esteemed it a privilege to battle against the errors of the fashionable mode of instructing females.” In 1832, she moved with her family to property close to the new town of LaGrange and continued her education, presumably at the new Brownwood Institute.

It was during this time that she became better acquainted with her cousin Blount Ferrell, whom she married in 1835 after a secret, but sweetly romantic courtship. Their marriage was by all accounts happy and successful; a union that eventually carried them through perilous times and personal tragedy, characterized by mutual support for the efforts and activities of the other. Within this secure relationship, they began their family, eventually returning to Troup County after a brief time in north Florida to establish a home on the crest of a parcel of land gifted to them by her father. While her husband built his law career and directed his agricultural enterprise, Mrs. Ferrell managed their household and followed her passions—supporting religious and academic education for young women, her devout faith and service to her church, constant charitable work, and the carving out of an eventual masterpiece garden on the terraced acres that sloped southward from their dwelling. Sources indicate that her mother, Nancy, was an accomplished gardener and that the two of them had a genial competition of sorts in what was deemed a “lovely pursuit.” It is probable that her mother shared plants with her, at least when the beds and borders of the couple’s new home were first established. They named their estate ‘The Terraces’, and as the scope and scale of her design evolved and a truly remarkable variety of botanical specimens were regularly added, it became evident that Sarah matured into an accomplished plantswoman. The travels of plant explorers to other continents in the 17th and 18th centuries had steadily increased and then surged in the 19th century, providing an ever-increasing array of new and exotic plants for enthusiasts of means. One early news article describing the elaborate grounds of The Terraces is dated in 1888 and contains an account of the rare plants and trees including calla lily, nun’s orchid, caladiums, a variety of magnolias, banana shrub, weeping arborvitae, Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria), Japan plum (loquat), weeping cypress, rhododendron, linden, China fur (Cunninghamia), and “one of the kind of trees that are the wonder of California.” One assumption is that the “wonder” was a species of Sequoia. Other sources note her more than coincidental placement of plants mentioned in scripture such as the “cedar, the shittah tree, and the myrtle…the fir tree, and the pine and the box tree together” found in verses from Isaiah.

However, what Sarah Ferrell primarily accomplished besides a very impressive collection for her times, was a work of horticultural art that expressed her deep convictions and thoughts. Her worldview, captured in sinuous lines of boxwood that spell out ‘GOD’ in one area, her personal motto of ‘GOD IS LOVE’ in another, and a garden room representing a church sanctuary–just to name some examples that are still here, reminders of her earnest spirituality. It remains as a living testimony, carefully preserved by the Callaway family that succeeded this remarkable woman. Much more could be said, as this is only a brief telling of her story, but words on a page cannot compete with tangible experience. It’s time for a garden walk with her, don’t you agree?

Portrait photo of Sarah Coleman Ferrell and her husband Blount. Circa 1860. Courtesy Troup County Archives. |

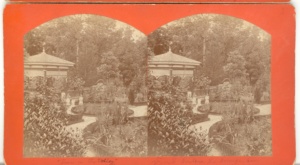

The summer house in the sunken garden. Stereograph by M. G. Greene. |

Sarah and Blount Ferrell on the porch with family members. Stereograph by M. G. Greene. |

Sarah, and Blount with family members in the garden near the well. Stereoscope by M. G. Greene. |

Visitor’s stroll along the path in Ferrell Gardens. Stereoscope by M. G. Greene. |

This 1930s postcard depicts Sarah’s motto, “God is Love”, made out of boxwood. The motto is still visible in the garden today. |

Sarah Ferrell was an important benefactor and supporter of Southern Female College. This rare photo shows a graduation ceremony in the late 1800s. A portion of the Sarah Ferrell Lyceum can be seen on the left. Courtesy Troup County Archives. |

View this entire Portico Newsletter: